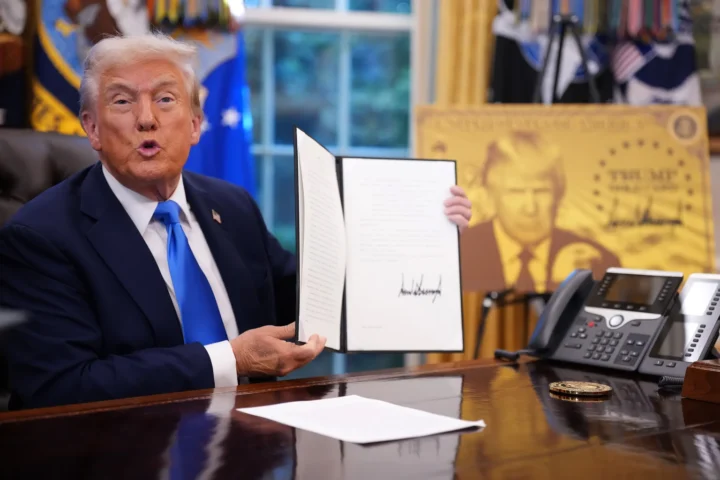

South Korea’s industry minister has made it clear that while Seoul’s recent negotiations with Washington softened the blow of U.S. trade measures, exporters are far from safe. The United States had been weighing a 25% tariff on a wide range of Korean goods, a move that would have hit manufacturing exports hard. After weeks of back-and-forth, the two sides reached a political understanding to set the rate at 15% instead. The agreement, however, is not a fully signed and ratified trade pact—meaning the fine print on product scope, enforcement, and review clauses is still being hammered out.

For Minister Kim Jung-kwan, the numbers tell the story: even a 15% tariff on high-value goods chips away at competitiveness in the U.S., South Korea’s second-largest export market. While the government is framing the deal as a relief compared to the initial threat, Kim is warning that exporters—especially smaller companies—will feel the squeeze.

Linking Tariffs to Investment

The tariff arrangement is tied to a broader investment and industrial cooperation package between Seoul and Washington. As part of the talks, South Korea pledged billions in new investments, particularly in U.S.-based semiconductor fabs, battery manufacturing, and clean energy projects. Officials have touted this as a way to strengthen strategic ties and create new opportunities for Korean companies within U.S. borders.

But these investments are a long-term play. For companies shipping finished goods from South Korea today, the reality is stark: the cost of exporting just went up, and unless they can pass those costs onto buyers—a tough ask in competitive markets—profit margins will take a hit.

Uneven Impact Across Industries

The tariff’s effects won’t be uniform. Automakers and steel producers are bracing for the sharpest impact, as these sectors fall directly under the tariff schedule and compete on thin margins. Korea’s flagship car manufacturers have U.S. plants, but their domestic production destined for America will be less price-competitive. Steel producers face similar challenges, especially smaller mills without U.S. subsidiaries or joint ventures.

On the other hand, sectors like semiconductors and pharmaceuticals appear to have avoided the brunt of the tariff impact. Washington has shown willingness to keep these industries insulated due to their strategic importance in global supply chains. Shipbuilding, too, may benefit indirectly from increased defense and infrastructure cooperation between the two allies. Still, the gains in these areas will not fully offset the losses in other manufacturing sectors.

The SME Pressure Point

Large conglomerates—South Korea’s chaebol—have ways to mitigate tariff costs, from shifting production to existing U.S. facilities to leveraging long-term contracts. Small and medium-sized enterprises, however, lack that flexibility. These firms often operate with tight cash flows, and a 15% price disadvantage in the U.S. can wipe out their operating margins entirely.

Some may resort to routing exports through U.S.-based partners or distributors, sacrificing revenue share in the process. Others will face hard choices between scaling back production, laying off staff, or finding alternative markets. The industry ministry is now holding emergency consultations with business groups and economists to identify possible relief measures, including tax incentives, low-interest loans, and government-backed export insurance.

Domestic and Political Calculations

The tariff compromise reflects more than economics—it’s also about geopolitics. The U.S. is pushing to re-shape global supply chains in critical industries, and South Korea is a key partner in that strategy. By accepting a reduced but still significant tariff, Seoul avoided a trade confrontation that could have spilled over into defense and technology cooperation.

However, the political cost at home is real. South Korea’s export-driven economy depends heavily on access to major markets, and many regional economies—particularly those built around steel, automotive parts, and machinery—are already feeling pressure from slowing global demand. Balancing alliance commitments with domestic economic stability will be one of the government’s toughest challenges in the months ahead.

What Comes Next

The most pressing issue is finalizing the written terms of the agreement. Without clear definitions on which goods are covered, when the tariff schedule might be reviewed, and how exemptions could be granted, uncertainty will linger for exporters and investors alike.

In parallel, Seoul is exploring mitigation strategies. These could include direct subsidies for tariff-hit industries, expanded trade finance support, and accelerated programs to help companies establish a production footprint in the U.S. Additionally, government agencies are encouraging firms to diversify their export markets to reduce reliance on any single country—though such shifts take time and investment.

Market watchers are also paying close attention to whether other U.S. trade partners secure better terms. If competitors like Japan or the EU receive more favorable tariff rates, Korean exporters could lose market share. Similarly, a change in U.S. trade policy under a future administration could either ease or tighten restrictions, making adaptability key for Korean companies.

An Uneasy Middle Ground

For now, South Korea’s exporters are operating in a middle ground—avoiding the worst-case 25% tariff but still grappling with a 15% cost burden that will shape pricing, profitability, and strategic planning. The industry minister’s warning is clear: while the government may have won breathing room in negotiations, the clock is ticking for companies to adjust.

The coming months will test how quickly South Korean exporters can adapt to this new trade reality, and whether government support measures can meaningfully offset the pressure. The stakes are high—not only for corporate earnings and jobs, but for the broader economic relationship between Seoul and Washington.